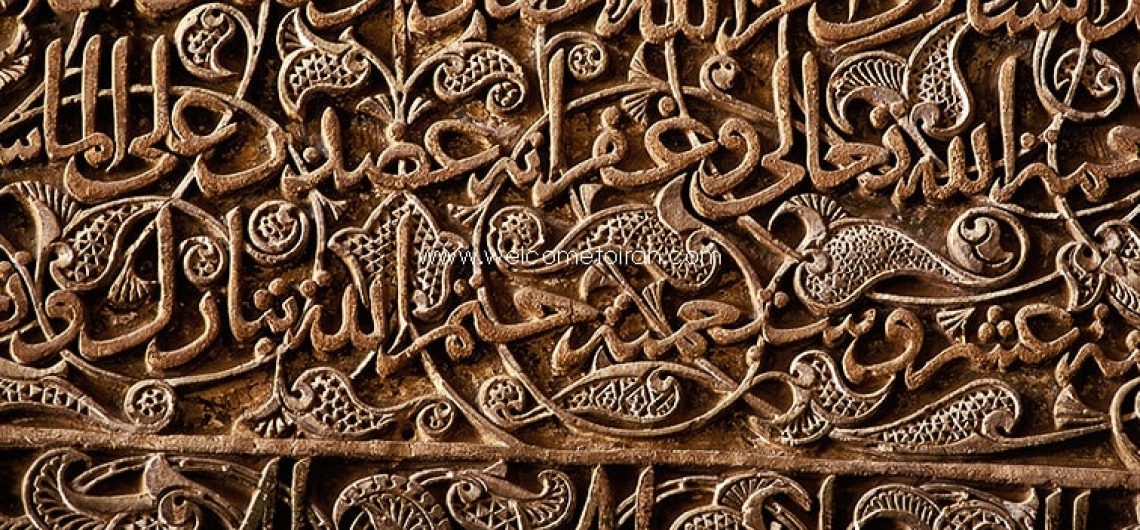

GACH-BORI, plasterwork or stucco, has been used as a building material in Persia for more than 2,500 years. Originally it may have been applied as a rendering to mud brick walls to protect them from the weather, but it was soon exploited for its decorative effects, as it alleviates the bleakness of brick and rubble walls and provides a ground for applied decoration. A cheap and flexible medium of decoration, it can be secured to almost any material of construction used for exterior and interior surfaces and can be molded, carved, and painted in a wide variety of ways. Stucco was also used for window and balcony grilles and to construct muqarnas (stalactite) vaults. In the hands of Persian craftsmen, this humble material reached unsurpassed heights of artistic creativity.

Stucco (plaster, painted plaster, gachbori), a versatile medium of decoration, though not unknown in earlier periods in Persia, was widely used from the Parthian until the late Qajar periods in all types of architecture.

Gypsum, the mineral from which plaster is made, was widely available. Traditionally, the quarried gypsum was sent on donkey back to the kiln where it was burned, crushed with wooden mallets to the size of hazelnuts, and pulverized in a edge–runner mill. Persian gypsum sets rapidly after being mixed with water, so to make it workable the mixture must be stirred constantly until it loses most of its setting power. This “killed” plaster (gach-e koshte) is applied to walls and ceilings in several coats and does not set hard for forty-eight hours. For fine stucco work, the wet plaster is dusted with powdered talc and gypsum and then rubbed to give a high gloss. For painted surfaces, the plaster is soaked with linseed oil and coated with sandarac oil.

Plaster, known as early as the Neolithic period, became common by Achaemenid times. Achaemenid palaces at Persepolis had brick walls rendered with a fairly thick coat of plaster, which was often painted with earth colors, and the columns of the Treasury Hall had a plaster coating applied to a layer of reed rope coiled around the wooden core.

The Islamic period. While Sasanian stucco was to a large extent molded, especially as square plaques used in a repetitive manner, Islamic stucco was carved by hand. After the end of the Sasanian empire, a number of buildings in the Ray-Varamin region underwent changes in their architectural decoration during the Omayyad period which seem to hint at both a continuity and a change.

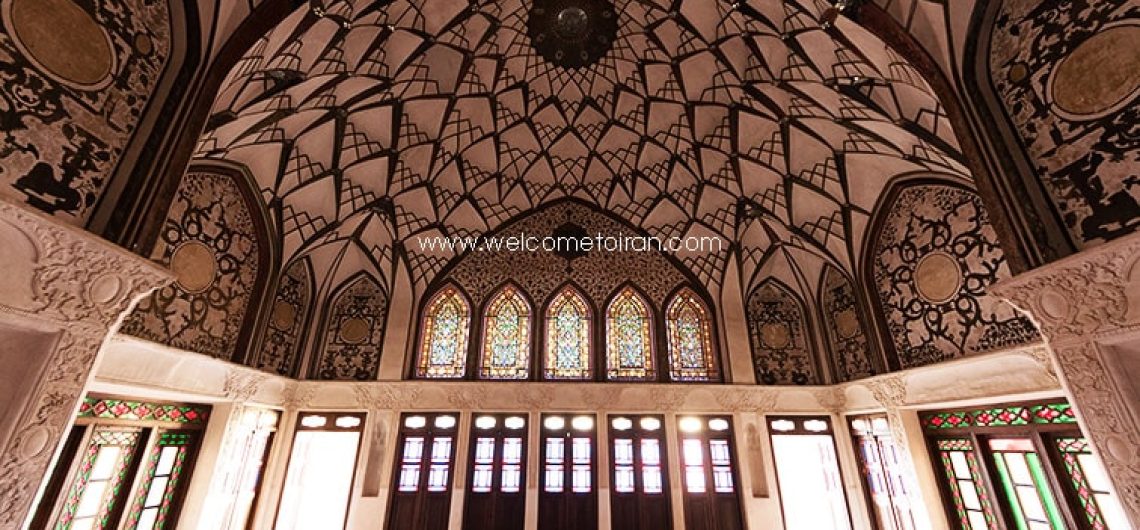

Mirror Work

Art of mirrors is surely one of the most delicate architectural decorations in Islamic-Iranian civilization. It is an art defined as forming regulated shapes in various designs and images with small and big pieces of mirror, for decorating interior surfaces of a construction. This artistic style, gives way to a bright and highly shining atmosphere created upon consecutive reflections of light in numerous mirror pieces. As the historical texts testify, this fine and delicate art is surely an invention of Iranian architectures. It seems that some researchers attribute the first appearance of art of mirrors in Iranian architecture in decorating the Porch House of Shah Tahmasib Safavid (1524-1576 A.D.) in Qazvin.

This art that seems, like other Iranian architectural inventions to be invented by the Iranian genius architectures kept moving in the post Safavid era and reached its climax at Ghajar era in constructing saloons like Mirror Saloon of Golestan Palace and especially in constructing religious and holy monuments. In this period, some amazing and exceptional buildings such as Darolsiadah at Astan Ghods Razavi (in 1275 Hejira), Darolsoroor at Hazrat Masoumeh (peace be upon her) shrine in Qum and the architecture of roof of Imam Reza (peace be upon him) shrine, were constructed by using art of mirrors. It was in the very period that small pieces of mirrors in triangle, rhombus, hexagon, etc. Shapes were widely used instead of applying big and flat ones though application of this method dates back to applying colorful rhombus-like glasses and small pieces of mirrors to decorate the roof and walls of the porch and saloon in addition to applying full-length mirrors at Chehelsotoon Palace. As Olearious has mentioned applying some hundreds of small pieces of mirrors in a regular and so artistic way in his account.

Tools and Materials Working Mirror Work

Materials used in mirror art include glue mirrors, isinglass glue and soft plaster. The tools used in the mirror art include design pens, a wooden ruler for putting on a glass, a table under the hand, a glass cutter

Mirrors were very significant and unique metaphors in theosophical and mystical texts in clarifying the proportion between the Right and the creation or manifestation of plurality from unity, and Einol Ghozat Hamedani believed it was merely through mirrors that the Divine beauty and majesty could be realized and studied:

“Alas! You do not percept what I mean. God is light of heavens and earth. The beauty of the prophet Mohammad is merely seen by mirror otherwise, eyes would burn. By mirror, the beauty of sun could be constantly studied and since it is impossible to see the beloved without mirror, she should be seen veiled. Love is doomed to be veiled and mirror is nothing but the majesty and greatness of God”

The Mirror Hall in Golestan Palace

The hall has been renowned as the Mirror Hall for its exquisite mirroring on walls and ceilings, which lasted for four years under the supervision of Iranian artists. On the mirrors, there is a beautiful Stucco art. The carpet of this hall is one of the masterpieces of carpet art in Mashhad, 70 square meters, 70 rows, is of the works of Abdull Mohammad Amo’oqli.